The Operatic Cinema of Lars von Trier

Filmmaker Lars von Trier isn’t German. He’s Danish. But it’s easy to mistake his nationality. Technically, he has some German ancestry. Many of his movies are set or shot in Germany, and he’s held a lifelong fascination for all things Deutsch. Take that “von” in the middle of his name—it’s a mark of aristocracy in Germany and Austria. Born Lars Trier in 1956 in a suburb of Copenhagen, he bestowed the “von” upon himself as a young man, an expression of what he called an inner “nobility of the spirit.”

This name-change—half-joking, half-serious—encapsulates von Trier’s most notorious qualities: his tendency to provoke; his constant need to reinvent himself; and his grandiose, sometimes megalomaniacal ambition. The closest personality on these proportions is, unsurprisingly, a German: Richard Wagner. Von Trier is a great admirer of the composer, whose epic music dramas have rubbed off on his films. In turn, von Trier’s cinema has inspired a string of recent operatic adaptations like Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek’s Breaking the Waves.

Von Trier’s first commercial films of the 1980s and early ’90 were, like Wagner’s operas, virtuosic displays of illusion. His methods were highly reminiscent of Wagnerian stagecraft—von Trier employed the technical aspects of cinema to generate a mesmerizing and all-absorbing experience. He would even blast recordings of Parsifal and Tristan during shoots to set a phantasmagorical mood.

While these early films were visually impressive, they were rather cold and lifeless. This stemmed from von Trier’s obsession with control. He meticulously storyboarded every frame and treated actors as mere puppets in his creations. To free himself of this perfectionism, von Trier took a counterintuitive step in the mid-1990s by drafting a set of rules. Titled “Dogma 95,” this manifesto consisted of ten commandments designed to strip away the fluff of filmmaking and prioritize the storytelling. All filming had to be done on location with handheld cameras. Special effects were forbidden. No soundtrack could be added during post-production.

The rules weren’t intended to be used in every film. Von Trier only made one pure Dogma 95 movie, his controversial The Idiots (1998). But all his films from that point on showed the influence of this cinematic “Vow of Chastity.” It completely transformed his style—the up-close-and-personal camerawork lent his movies a new rawness and immediacy. His stories, too, became more human, his characters more vulnerable.

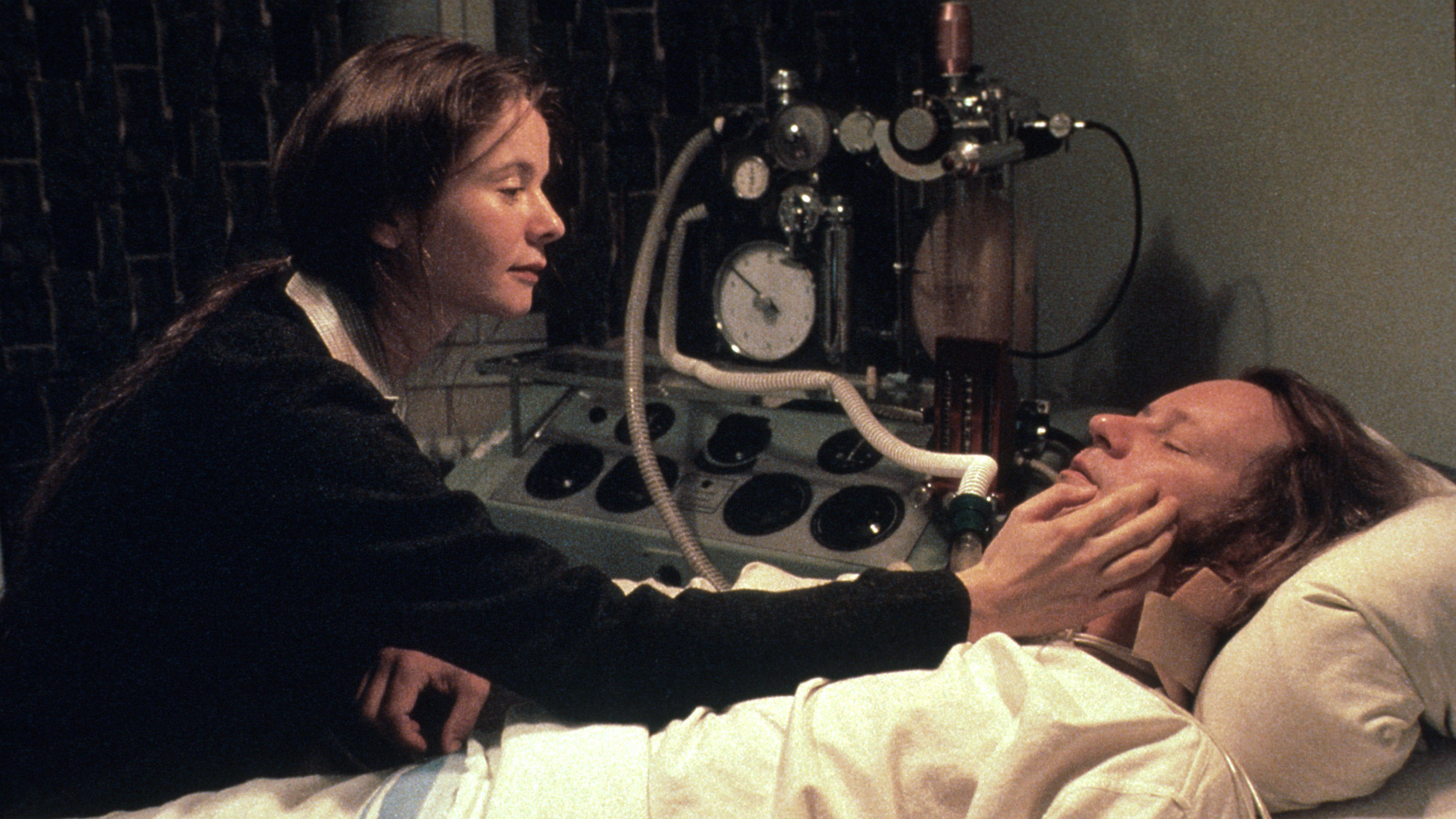

This was a deliberate rebellion against the values instilled by von Trier’s hyper-progressive parents, who forbade anything that smacked of sentimentality. In films like Breaking the Waves (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000), he fully embraced the tragic and the pitiful, pushing his heroines to impossible extremes. These two films, along with The Idiots, formed von Trier’s “Golden Heart Trilogy,” named after a Danish picture-book from his childhood. In the story, a little girl gradually gives up her clothing to the needy until she’s left naked and cold. Similarly, von Trier’s trilogy depicts women who hold unwaveringly to their moral convictions, to the point of destroying themselves.

The emotional intensity of these films, while overwhelming and even uncomfortable to witness onscreen, is right at home in another medium: opera. Von Trier even declared he was striving for “something that is more like the emotion of an opera” with these melodramas. It’s no wonder, then, that composers and librettists have been drawn to his films as the basis for operas.

Operatic adaptions of films have become increasingly common in the last decades. HGO commissioned two such works: André Previn’s Brief Encounter (2009) and Jake Heggie’s It’s a Wonderful Life (2016), both based on classic flicks of the ’40s. Typically, composers gravitate toward films with minimal or forgettable soundtracks, so as not to erase the work of a fellow artist.

It’s unusual, then, that two of the three major von Trier-inspired operas are based on films that already feature iconic scores. The 2007 Selma Ježková, by Danish composer Poul Ruders, is an operatic take on Dancer in the Dark—itself a movie-musical with songs by its leading lady, Björk. And von Trier’s Melancholia (2011), which makes exquisite use of Wagner’s Tristan prelude, was set as an opera by Swedish composer Mikael Karlsson in 2023.

By contrast, music is all but absent from von Trier’s Breaking the Waves—a holdover from the Dogma 95 stricture on soundtracks. Each chapter of the film opens with a title card displaying a sublime landscape on Scotland’s Isle of Skye, where the film takes place. To evoke the time setting, these panoramic views are paired with short clips of hits by 1970s rockstars like David Bowie and Elton John. Otherwise, the movie is—sonically speaking—a blank canvas for a composer like Missy Mazzoli to paint on.

What’s more, the screenplay is highly reminiscent of standard operas. The Scottish environs as well as the heroine’s struggle against her patriarchal oppressors recall Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. And Britten’s Peter Grimes, with its small-minded, seaside village and outcast protagonist, also contains parallels. But given von Trier’s operatic tastes, it’s most likely that the filmmaker was influenced by Wagner’s music dramas. Bess’s final act resembles the redemptive self-sacrifices of Wagnerian heroines: Senta in The Flying Dutchman, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Brünnhilde in Götterdämmerung, Kundry in Parsifal.

But even if the original film is intentionally operatic in tone and scope, a screenplay can’t simply be set to music as a libretto. There are forms and conventions that have to be followed when transferring a celluloid work to live theater. In his adaptation, librettist Royce Vavrek seizes on some of the more idiomatically operatic moments of the film. For instance, he expands the phone-sex scene into a full-fledged love duet. While Bess and Jan are separated during this sequence in the film—both physically and through editing—the characters are able to embrace onstage in Tom Morris’s production of the opera.

Vavrek also endows the libretto with a poetic sensibility that’s lacking in von Trier’s script. The other love duet, following Bess and Jan’s wedding, is an entirely new text of Vavrek’s invention. Its central metaphor—that the couple’s life paths are mapped out on the lines and contours of Jan’s body—is the kind of lyrical language that’s out of place in realist cinema, but essential in opera to fire a composer’s imagination.

Even if the original film is almost completely devoid of music, it’s rife with opportunities for an attentive composer like Mazzoli to bring to sonic life. During the church scenes in the opera, for instance, the Calvinist elders intone their admonitions in austere, hymnlike harmonies. In a nod to von Trier’s title-card interludes, Bess dances to a convincing pastiche of a ’70s pop tune. The bells that the congregation cast into the sea are mostly absent from Mazzoli’s orchestration, only symbolically imitated by different instruments. In a highly original move, Mazzoli also evokes bells vocally in Bess’s ebullient opening aria. She repeats Jan’s name over and over with all the brightness of a ringing church chime.

One of the most fascinating compositional devices in the opera is the ever-present male chorus, which looms over Bess like the imposing pillars of Soutra Gilmour’s set. They alternately portray the congregation elders, the oil-riggers, and the men of the village. Elsewhere, they stand in for the ultimate patriarchal authority: God himself.

In the original film, Bess’s prayers take the form of a one-sided dialogue. The character answers her own petitions with the gruff, paternal voice she imagines belonging to the Almighty. In the opera, Bess’s “God voice” is amplified and echoed by the male choristers. It’s a nod to Arnold Schoenberg’s 1957 biblical opera Moses und Aron, in which the voice of God is assigned to an unseen chorus.

Then there are the waves of von Trier’s title. Mazzoli doesn’t take this literally—she largely avoids any buoyant aquatic textures redolent of Debussy or Britten’s sonic seascapes. Yet there are passages when we might hear metaphorical waves in the orchestra’s endlessly descending scales. By staggering these plunging lines in different instrumental voices, Mazzoli creates the impression of a vortex or undercurrent pulling us toward oblivion. It’s a striking musical representation of Bess’s downward spiral.

Bess herself is a frustrating character who has raised debate among feminist film critics and religious-studies scholars alike. Von Trier defended himself against charges of misogyny by pointing out that Bess is ultimately in control of her own fate and goes willingly to her demise out of boundless love for Jan. Yet there’s a disturbing uncertainty about the story. Do we take it on faith that Bess truly possessed saintlike powers of healing? Or have we witnessed a vulnerable woman fall victim to the abuses of the men around her—including her husband and her warped conception of God?

Von Trier’s distaste for soundtracks stems from his irritation with directors who employ a film’s score to manipulate viewers emotionally. In this sense, Mazzoli is the ideal composer to adapt his work. She’s by no means unsympathetic toward the characters. But her musical language, indebted to the post-minimalist style of John Adams, leaves ample space for interpretation. Her harmonies, in particular, are shrouded in ambiguity. Mazzoli sends out progressions that never seem to settle on any firm resolution. She will often pivot unexpectedly from a major chord to its minor version, producing a subtle yet strangely disorienting shift in affect. Or else, she’ll allow these two incompatible harmonies to hang in the air simultaneously—apprehensive, irreconcilable, inconclusive.

Mazzoli’s score is visceral and psychologically probing, but in the spirit of von Trier’s film, it doesn’t tell audiences how to think. Instead, the opera confronts us with insolvable dilemmas, forcing us to reconceive our views on morality, spirituality, and sexuality. But ultimately, Breaking the Waves—like every lasting work of opera—is a profound meditation on the greatest mystery of all: what it means to love another person. As Bess puts it, “That is perfection.”