Your Love Is Your Life — Houston Grand Opera’s 2024-25 Season

“When love comes so strong, there is no right or wrong.

Your love is your life.”

—From West Side Story, Leonard Bernstein/Stephen Sondheim

Over many years now of talking about upcoming opera seasons and all of the artists within them, I realize how much time we spend speaking about composers—which must feel slightly perplexing and probably off-putting to many people.

After all, when we think of our favorite lines from movies, our strong tendency is to associate them with the actor who said them rather than the author who wrote them. For example, it was the veteran actor Alec Guinness, playing Obi-Wan-Kenobi, who first uttered the line, “May the Force be with you” in 1977’s iconic Star Wars, and he was associated with it for the rest of his life, but it was George Lucas who wrote the line. Audiences get to choose how deeply they care about these things.

What we engage in with all operas is, first and foremost, a composer’s voice. All other voices—those of singers, conductors, directors, and the huge army of artisans it takes to form a company capable of works like Il trovatore or Tannhäuser at all—lend their own voices to the composer’s. What has kept West Side Story and La bohème forever in front of generations of music lovers is, obviously, music…it is fair to say that almost no one attends them to see how they end. Composers’ voices keep us going: they are in every board meeting, every budget meeting, every casting idea, and every ounce of excitement about a new season.

In any given opera season, there are so many artists to whom we attach our affection and expectation. Next year alone, here are some of the singers we have engaged, each of whom took many years to secure:

Michael Spyres (surely one of the greatest singers in front of the public right now)

Ailyn Pérez (so soon after her triumphant Madame Butterfly!),

Isabel Leonard, (utterly a star!)

Raehann Bryce-Davis (is there a more distinctive voice in the world right now?)

Lucas Meachem (charm and stentorian sound—amazing!)

Jack Swanson (effortlessly tossing off Rossini’s death-defying roulades)

Alessandro Corbelli (the very best in the world at an ever-rarer art: basso-buffo comic roles)

Russell Thomas (is there a more beautiful voice anywhere?)

Tamara Wilson (superlatives fail—her artistry sits in the pantheon already, and she’s only getting started on Wagner)

And Sasha Cook, Ryan McKinny, Lauren Snouffer, Ana María Martínez, each of them special to the company. I think of the HGO debut of the extraordinarily gifted Yaritza Véliz as Mimì in La bohème alongside Joshua Guerrero as her Rodolfo, or the ardent Luke Sutliff singing the great “Evening Star” aria in Tannhäuser, and all of the youthful energy of next season springs to life all over again.

I think of the directors and conductors, each of them cherished colleagues, and most especially the return to HGO of Stephen Wadsworth, one of the under-sung geniuses of opera in America, directing a new Trovatore with his rare rigor and theatricality. Our marvelous guest conductors will bring a world of perspective to our podium, and thus to the voices of composers.

Our current 2023-24 Houston Grand Opera season, just over halfway completed, has been weighted with the mature works of composers, including the final operas of two titans, Verdi’s Falstaff and Wagner’s Parsifal, each written within a decade of the other, and each so different. They are perfect testaments to the breadth of the operatic medium. Our upcoming spring repertoire is also a bit of genre-perfection, because neither Don Giovanni nor The Sound of Music were called operas by their creators. Here again, the scope of a company’s work easily encompasses both Mozart and Da Ponte’s great allegory of guilt, Don Giovanni, as well as the final collaboration of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s historic partnership, a throwback to the operettas of their youth, The Sound of Music.

By contrast, the new season we’re announcing for 2024-25 is not only largely about young love, but the operas themselves were composed by youngsters—Rossini, for example, was in his early twenties when he began his beloved Cinderella, and West Side Story’s lyricist Stephen Sondheim was only 24 when he signed onto the project. Artistic babies! The boundless energy of youth runs through each of next year’s works: Tannhäuser, though not Wagner’s first opera, was his first grandly romantic work in the style for which he would change the world. Il trovatore was a breakthrough opera for the young Verdi, as was Breaking the Waves for the preternaturally gifted young Missy Mazzoli, and the two operas are similarly shocking for, and of, their eras.

Love is probably not thought to be a very groundbreaking subject for a work of art. Aren’t most works of art somehow about love? Yes and no. Few operas lack a love theme, but never in one season have so many of our operas taken such diverse views of what love means. West Side Story deals with violent and fatal love, the consequences of blind hatred—just as did its source play, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, in which a relationship lasting only a few days results in multiple deaths. And La bohème presents the innocent love of youth, and a bunch of teenagers searching for who they are, until tragedy intrudes upon their world. There are so many ways to view universal feelings, and opera’s enlarging totality is perfect for the subject of love.

Il trovatore

If you are an opera lover, you have a soft spot, or you need one, for Verdi’s Il trovatore, because it is a score of scores—the Verdi-est of all of the Verdi operas—the ultimate Italian opera, with everything that means. Why? Because Trovatore is archetypal heaven: the most romantic of all heroes in Manrico, the most faithful of all heroines in Leonora, the most villainous of jealous villains in the Count, and by far the most compelling of Verdi’s “other” characters, in Azucena.

Trovatore also shares unique qualities with two other popular Verdi operas of its era, Rigoletto and La traviata: each has a major character who is invisible and only sung about. In Rigoletto, we hear often of the title character’s wife, Gilda’s mother, most compellingly in the opera’s final moments, but we never know her—the same with Alfredo’s sister, around whom the entire plot of La traviata turns. Il trovatore is entirely about avenging a wronged mother, the mother of the character of Azucena, the invisible presence who motivates every moment of the action.

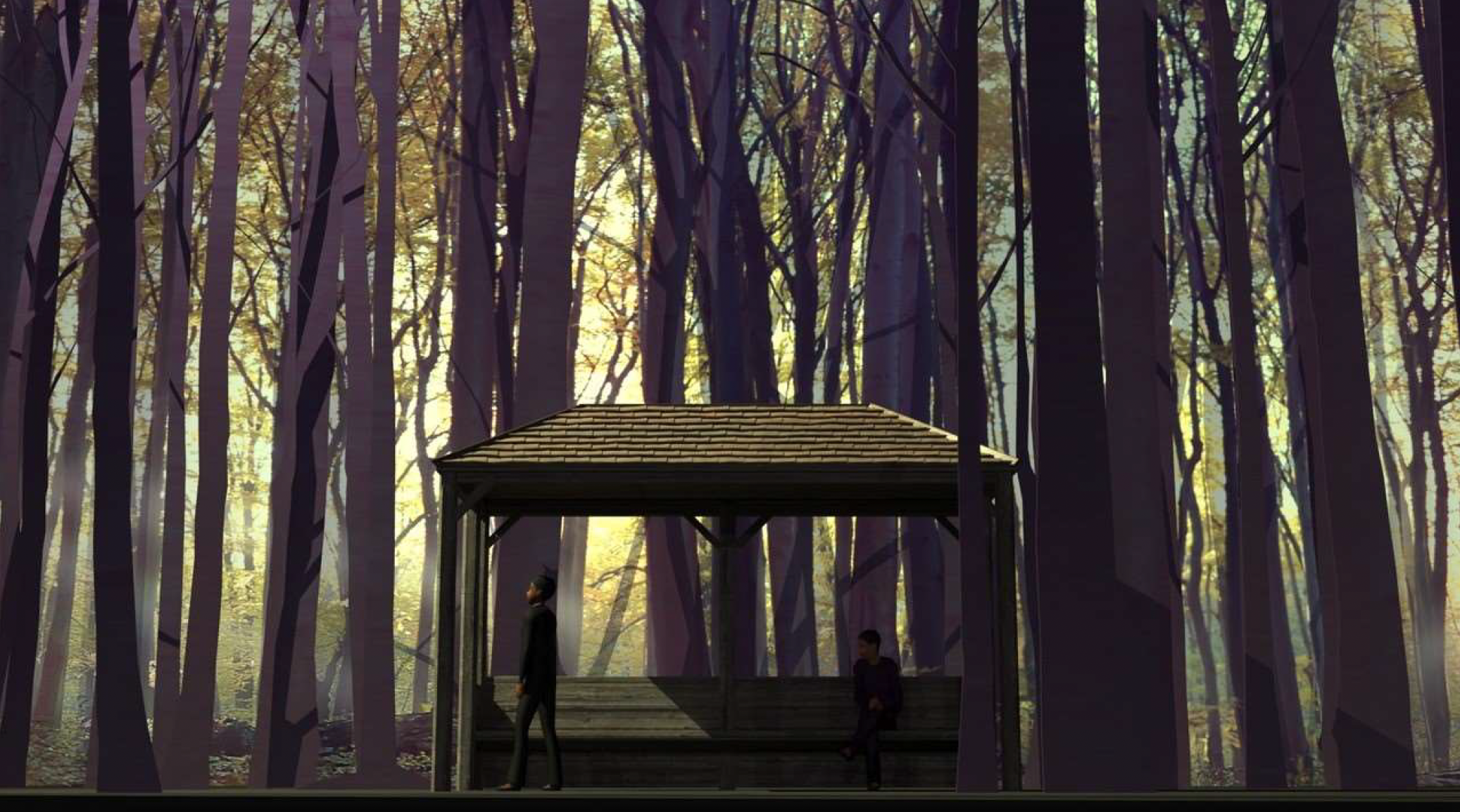

Trovatore has a famously convoluted and melodramatic plot, but in truth, though it is sensationalist, it isn’t at all implausible. One look at any current news source will prove that. A child dying by a mother’s hand is, of course, a horrific subject for anything, but it sadly cannot be said to be unbelievable. Stephen Wadsworth’s new production will be more contemporary than is usual for this opera, but it lives in the uneasy space of old and new that we so often encounter in life now.

The character of Azucena was what drew Verdi to the subject in the first place, and she would have been known in Verdi’s time as a gypsy. The Romani people lived nomadic lives, branching out from Rajasthan centuries ago, and were particularly present in 19th-century Europe, and thus the subject of much lore. Since the World Romani Conference in 1971, the Romani have openly rejected all nomenclature describing their heritage, including the word gypsy, which they find demeaning. Verdi and his librettists, Cammarano and Badere, long predated these nuances, of course, so there is always tension between old and new simply in what we call her. She is, from our 2024 perspective, Romaní.

Il trovatore has an extremely formal construction, which is one of the reasons it has sometimes been the subject of ridicule. Also, The Marx Brothers 1935 film, A Night at the Opera, is perhaps the biggest reason that Trovatore is thought to be on the silly side. And speaking of youth, the play upon which Verdi’s Il trovatore is based, El trovador, was written by the 22-year-old Antonio Garcia Guttierez, one of Spain’s most influential Romantic novelists. The caloric plot is his invention, and the dramatic device of stolen children was a common one at the time and even earlier: the plot of The Marriage of Figaro also revolves around Figaro being stolen from his real parents.

Verdi was also hoping to capitalize on the plot of an opera that was very famous when he composed Il trovatore, Halevy’s La Juive, a well-known hit, with a plot significantly more fantastical than Verdi’s opera. Again the composer’s voice comes back to our minds: Trovatore is still beloved by opera lovers, while La Juive is an extreme rarity. The composer’s voice is the reason. Il trovatore has a rich and deep operatic history, and the score—well—it is simply one of the miracles of our art. It sweeps us along with Shakespearean power.

Cinderella

This is a story told in many languages and beloved in all of them. The famous girl of the ashes is Cenicienta in Spanish, huī gū niang in Chinese, Zolushka in Russian, Aschenputtel in German, Cendrillon in French, La Cenerentola in Italian and, immortalized in English-language fairytales as Cinderella.

She is a story for the ages because hers is a story that needs constant re-learning. Rossini’s Cinderella is one of the most ebullient tellings of it, and as an opera it is a very human comedy, delightful, tuneful, toe-tapping, sweet, and touching. It tells us, at some fundamental level, how to live, because in the opera life’s most important qualities are emphasized and brought to humor: forgiveness and goodness are better for the world than their opposites. The music is like a glass of the lightest champagne.

Though Rossini was very young when he composed Cinderella, it was his 20th opera. The score bubbles with life, with one of opera’s famous “frozen” moments in the second act quintet—a long passage about the situation being a terrible tangle, a knot, and we both hear and see it in Rossini’s music.

The end of Rossini’s opera, the famous “non piu mesta” (no more tears) aria, is a ray of golden sunlight after a long storm. There are few moments as moving. Were I looking for a single moment upon which to hang my hopes for next year, it would be that one.

Two tragic love stories make up our winter season:

La bohème

and

West Side Story

Near the end of the great duet between West Side Story’s leading female characters, “A Boy Like That,” Stephen Sondheim, the show’s lyricist, sums up the feeling we all carry away from any performance of West Side Story with a poet’s accuracy: “When love comes so strong, there is no right or wrong—your love is your life.” Every opera, play, or musical has a beating heart—this line is the beating heart of West Side Story.

This is a fair question to ask: does West Side Story belong in an opera house? The show had four creators: it was librettist Arthur Laurents who had the idea to create a modern re-telling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet set in New York City, though the initial idea was to have the warring Sharks and Jets be of rival religions rather than about immigrants. Composer Leonard Bernstein initially asked Oscar Hammerstein II to write the lyrics, but Hammerstein sensed that the project needed the energy of youth, and he recommended his young protégé Stephen Sondheim, a budding composer who would go on to re-shape the American musical more than anyone. The visionary choreographer Jerome Robbins gave dance a role it had almost never played in a musical before. So what is West Side Story? Bernstein’s score is certainly as demanding as any opera. Is it a ballet with singing? A play with dancing? An opera with dialogue?

Happily, categories only really matter to librarians who have to put books away on the right shelf. West Side Story is everything: play, ballet, opera, a brilliant totality that now—with the commercial realities of the world—needs the resources of an opera house to be realized as Bernstein imagined it. And how it soars when played and sung as it was intended.

One of the most illustrative stories about Puccini involves the titanic Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini. As the story goes, they once stopped overnight in a country town while Puccini was driving them from Milan to Rome and, noting a local presentation of La bohème, anonymously bought tickets. The performance was apparently dreadful, the singers impossible, the conductor clueless. The furious Toscanini, about to erupt, looked over at his friend Puccini only to find him awash in tears. “This performance is terrible! Why aren’t you furious?” stormed the Maestrissimo. “I know,” answered Puccini, “but what beautiful music!”

The story probably isn’t true, but it perfectly illustrates the position of Puccini in one of the curious class divisions within classical music. Any composer who has ever taken the courageous step of putting ink to paper would envy Puccini’s popularity; yet it is his very popularity that has made him strangely suspect to many, and it has often been in vogue to malign him. An Italian critic of the first production of La bohème in Turin claimed the opera would make no great impression upon the world, and suggested that Puccini should take up some other line of work before further embarrassing himself. This, too, is illustrative of an unfortunate trend in classical music that must always be fought: elitism. Opera would be far less rich without Puccini’s three most popular operas—La bohème, Madame Butterfly, and Tosca—and they are each extraordinary great works. So is Puccini’s masterpiece, his truly remarkable Trittico, which I dearly hope may finally be arriving at HGO in a future season.

Ever since Henri Murger’s novel Scenes de fa vie de bohème appeared in 1851, the stories of rebellious youth in the Latin Quarter of Paris have touched millions. Though in every major urban center in the world there were “bohemians”—writers and artists who, then as now, skirted the conventional rules of society—it is Rodolfo and Mimì who seem to have permanently captured our imaginations and hearts. The bohemians of Murger’s world were not poor. Rather, they were from well-heeled families, and rebelling against the type of comfortable life that made their rebellion possible at all. When reality intruded, as in the case of Mimì’s health, the bohemians were helpless.

La bohème perfectly marries music and words, so much so that it is quite impossible to speak of one without the other. Puccini sculpted the score and text with almost complete symmetry; nearly every image and situation happens twice, though the repetitions are subtle and some pass subliminally. For example, in Rodolfo’s soaring opening phrase, he sings of gazing out upon the Parisian rooftops; a short time later, Mimì mirrors the thought, but Puccini’s score this time is intimate and personal, a tender confession hinting that destiny is about to introduce two lovers.

The score is packed with musical and linguistic details and delights; rarely has music so clearly expressed the sheer exuberance of youth more clearly than in the opera’s energetic opening music. Each of the four bohemians has a unique musical personality. Rodolfo, the poet, is naturally the most ardent—and he only becomes a good poet when he gazes into Mimì’s eyes. She is his poetry. The painter Marcello’s music is filled with youthful dreams, and, ultimately, reality. Schaunard, the musician, often has the more elevated and verbose musical tone; and Colline, the philosopher, sings and speaks with the perfume of academia until real life comes crashing in and he touchingly become the human embodiment of his philosophies with a simple act of kindness.

The innocent and sweet Mimì is complemented by the worldly and fun-loving Musetta, who has the more earthbound and sensuous music. Musetta appears to live only on the surface of life, enjoying the attentions of wealthy men and aspects of Paris she could not afford without them. But she becomes the moral and human center of the opera’s finale, for only Musetta and Colline think to do anything practical or spiritual when the inevitable becomes clear. Puccini, forever at odds with his librettists, altered one detail in Act IV to very touching effect. Musetta has Marcello sell her earrings to buy a muff to warm Mimì’s cold hands, knowing it may be her last wish. Mimì asks Rodolfo if he purchased it for her. Before he can answer, Musetta answers for him that, yes, Rodolfo was the thoughtful one. Where lesser composers might have made a large moment of the gesture, Puccini wonderfully understates it. For all of the simple symbolism of the text, Puccini seems to have missed no detail in his score. He even depicts, with barely audible low-string pizzicato, Mimì’s slowly fading heartbeat.

Puccini’s opera may be the most famous artistic incarnation of the bohemian lifestyle, but it’s hardly the only one. His contemporary Ruggero Leoncavallo, the Italian composer of Pagliacci, claimed exclusive rights to the subject, but Puccini wrote his version anyway. The two composers’ creations were rivals for a time, before Leoncavallo’s faded into obscurity as Puccini’s captured the public’s affection like no opera before or since. The familiar bohemians starred in three silent films, the most famous from 1926 with Lillian Gish and John Gilbert, who in their day were as high in the firmament as Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor, stars of Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 hit Moulin Rouge!, the bohemians’ most recent cinematic incarnation. Moulin Rouge! combines La bohème’s plot with that of another 19th-century opera set in Paris—Verdi’s La traviata.

La bohème lives in front of a loving public because it reminds us of carefree and nostalgic days, and because its music has the warmth and honesty of youthful promise. The emotional world of this opera, through the perfection of its score, travels through many extremes, from the most outward expressions of pure joy to the most intimate moments of profound tragedy. La bohème reminds us of our youth even as it confronts us with the bittersweet realization that those days are behind us.

There is a perfection of a poem by Philip Larkin (1922-85) that completely captures the charm of Puccini’s most popular opera and explains our enduring affection for its tender appeal:

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word- the men

Leaving the gardens tidy.

The thousands of marriages

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

From MCMXIV (1914)

first published February 28, 1964,

in The Whitsun Weddings

The spring 2025 repertoire at HGO presents two emotionally epic operas about religious pilgrimage, each of them delving deeply into the uncomfortably unbridgeable worlds of spirituality and eroticism.

Breaking the Waves

Of operas written in recent years, few have brought such strong emotions as Breaking the Waves. Thrilling, disturbing, provocative, cathartic. This is not escapist art, by any means. Breaking the Waves is confronting and difficult, while being of extraordinary beauty.

The opera is based on Lars von Trier’s 1996 film of the same name, the first of his Golden Heart trilogy.

It recounts the story of Bess McNeill, a young Scottish woman suffering from an undisclosed mental illness. She falls in love with and marries an oil rig worker, Jan—pronounced “yawn”; the first sentence of the opera is “his name is Jan.” When her new husband is severely injured in an oil rig accident, she blames herself for praying for him to stop working on the rig.

Jan asks Bess to take other lovers and report the encounters back to him, as a way of keeping a level of intimacy with his wife. Feeling the guilt of his accident, she complies, and the opera is about her journey toward complete breakdown in the face of her new reality. It ends both tragically and beautifully, with the waves of the title broken.

Missy Mazzoli’s score for Breaking the Waves is of ethereal beauty, with a compelling sound world that takes us on a profound spiritual journey. Were I to choose a single opera I’m most looking forward to next season, it would be Breaking the Waves. Lauren Snouffer’s extraordinary artistry takes on the challenges of the vulnerable and complex Bess, with Ryan McKinny as Jan. This will be unforgettable.

Tannhäuser

There is very little in the operatic repertoire as thrilling as Tannhäuser, but, as usual with Wagner, he asks a great deal of both performers and audiences. Not that the opera is so long—it is actually amazing how short it is—but it is incredibly demanding, expensive, and thrilling to perform. Only a few companies in the world can deliver it.

Tannhäuser is the perfect company opera, because one of its main subjects is the art of singing itself. At its center is the famous song contest of the Wartburg, an area in the Thuringian valley in what is now central Germany. Wartburg Castle still towers over the area. To perform Tannhäuser well takes many years of ensemble-building, and many years of support from many people. It simply isn’t the sort of opera that can be put together hastily. Wagner’s score is legendarily gorgeous and soaring—one of the most beautiful ever composed for an opera.

Had Wagner only composed Tannhäuser, he would still have been one of the most consequential composers in history. It came early in his life, before Lohengrin, Tristan, Meistersinger, the four vast operas of the Ring, and Parsifal.

Tannhäuser comes from the world of the high Romantic era, and so it shares many qualities with works of that time: the worlds of E.T.A. Hoffmann, Goethe, and William Wordsworth, and Biedermeier furniture, still prized for its sensual overdone-ness. High romance, and the tension between the mind and heart, the intellect and the spirit, and faith and sensuality, were all hallmarks of this time—this was also the era of America’s Second Great Awakening, a movement that particularly fascinated Wagner, as well as the concurrent transcendentalist movement, led by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who Wagner’s early champion, Friedrich Nietzche, thought to be one of the few Americans of the time worth thinking about at all. Tannhäuser manages to contain pieces of all of these influences. The title character does not get redeemed by the Pope, despite the length of time in the opera spent on his pilgrimage to Rome—but the ending of Wagner’s Tannhäuser remains one of the most singularly thrilling spiritual transformations in any opera.

Wagner got the idea in 1841. He conceived the libretto and composed the opera within a few years, quite a short gestation period for him, considering that the Ring and Parsifal occupied him for 30-40 years. Much is made, too much, of the two distinct versions of Tannhäuser, composed for Paris and Dresden, and they are quite different operas, structurally, though the essential story is the same. The actual differences are of interest only to scholars—but what is more broadly fascinating is that this is the one opera Wagner thought he never finished. He remarked even in the days before his death in Venice in 1883 that he felt he stilled “owed the world a Tannhäuser,” so the opera’s subject clearly weighed on him. It can be a terrible feeling for an artist to have left something uncompleted.

But any single season, including the one we are announcing, has Wagner’s feeling of incompletion. There is just so much within it, not only the unique voices of the composers, but also the distinct connections of all of the artists to our company. Some of them are debuting, so their relationships with HGO are youthful. Some of them have appeared many times, and so represent deep artistic roots. They are from all over the world, for opera is a global art.

This coming season celebrates all that newness means, and we realize in the joy of all of these connections—composers to singers to conductors to directors to audiences—that love is the right subject all along, just as it should be.